Google has officially rolled out AMP (Accelerated Mobile Pages) in its mobile search results, and will favour those results over sites not using the AMP framework moving forward.

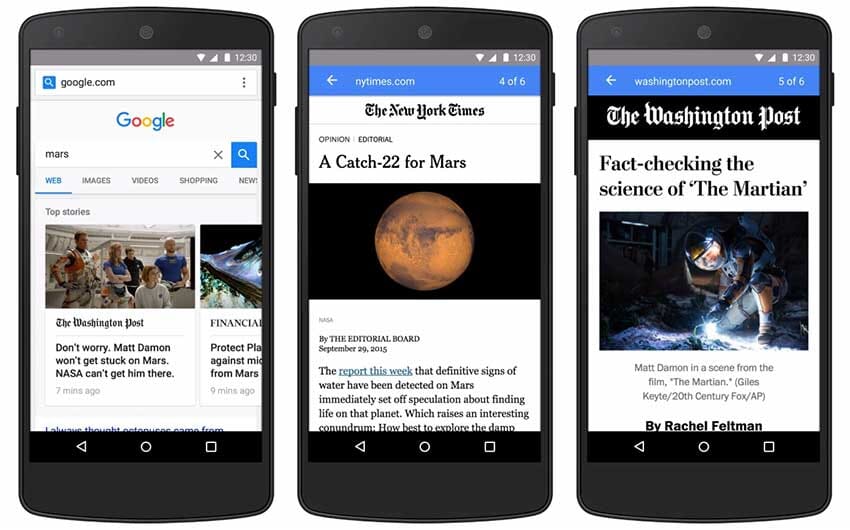

On February 24, 2016, Google officially rolled out AMP (Accelerated Mobile Pages) in its mobile search results, and will favor those results over sites not using the AMP framework moving forward. These mobile pages are Google’s answer to creating a faster – and hopefully more user-friendly – mobile web, designed to load nearly instantaneously. Google has started the roll-out with select news publishers such as The New York Times and Vox Media, with AMP-powered stories typically appearing at the top of a search result in mobile browsers.

The development of AMP is both a response to the ever-growing usage of mobile devices, pressure from Facebook and Apple, and further developments like Instant Articles, which hosts publisher content directly within Facebook. As mobile users increasingly spend more time in apps, Google has looked for ways to make the mobile web (and its app ecosystem) remain competitive: it has to be faster, less cluttered, and more reliable. Usage of its search engine and the prolific use of the open web, after all, is Google’s lifeblood.

A major challenge for publishers is that their sites traditionally do not perform well in a mobile context. Third party ad serving technologies require bandwidth and CPU power which drain a device’s battery. As users increasingly engage with this content on mobile devices, these performance issues create a bigger hindrance on the overall experience. AMP is essentially Google’s solution to help publishers push content in a mobile setting that will load unencumbered by elements that traditionally impede content performance.

What is AMP?

Facebook and Apple have launched their own closed-system platforms (Facebook Instant Articles and Apple News) to handle these issues that publishers have widely adopted. AMP serves as Google’s version of a mobile publishing project, but with some fundamental differences. At its core, AMP is a set of specifications, standards and technology that is not beholden to a closed system. These can be broken into three key areas:

- AMP HTML – A modified version of traditional HTML designed for the mobile experience; the code on which an AMP page is built.

- AMP Runtime – A JavaScript that provides further enhancement to the page’s load. This includes prioritising what images load, and ensuring content above the fold loads first.

- AMP Cache – While not a requirement, publishers can house AMP pages on Google’s CDN for free. Publishers can also use their own Content Distribution Network, but ultimately the purpose of this component is to ensure the content is loaded from the resource that will serve it quickest.

All of this represents a rather fundamental shift for Google, from indexing and pointing to content throughout the web to now setting a streamlined framework and actually hosting a portion of the content it serves. Google hopes that by creating a faster mobile web via AMP and favouring it in search results, publishers will adopt it en masse. Content created in the open-source AMP framework will be accessible anywhere – whether it be from the search engine or links on Pinterest, for example.

AMP is currently live on the mobile web only, but will be opened up to mobile apps soon.

Requirements for an AMP Page

AMP is open to anyone. From a requirement standpoint, the pages themselves must be created as their own entities (i.e. this cannot be appended to an existing article). WordPress has launched a plugin that generates an AMP version of pages that are published. By virtue of AMP HTML, some limitations exist. For example, the page cannot run unapproved JavaScript which will require publishers who rely on them for analytics code or ad serving to seek alternative methods. In addition, there are five ad generators supported by AMP, including A9, Ad Reactor, AdSense, AdTech and DoubleClick. Publishers using other platforms may need to consider switching in order to retain their revenue streams from this content.

Resolution POV

AMP-powered content is undoubtedly lightning-fast and will certainly make the user experience stronger on the mobile web. Users will also appreciate some of the standards embedded in AMP content – no pop-up ads and the incentive for publishers to focus on content. Google hopes that making a more standardised mobile web will mean that fewer people use ad-blocker apps on mobile devices, which obviously hurts their key revenue stream. While it’s clear that mobile user behaviour has become very app-centric, much of the content on the mobile Internet still relies heavily on the mobile web. From that perspective, it’s good to see Google get more involved in providing leadership on standards and incentives in the mobile web.

For publishers and businesses already grappling with the concurrent development of mobile sites and apps, this adds another dimension to their development efforts. Still a very new project, the success of AMP will depend on widespread adoption. Building AMP pages is a relatively straightforward endeavour but it does require heavy implementation (generating new/duplicate pages, hosting considerations etc.). To date, publishers will benefit the most from AMP as an initiative geared towards the news space. If a publisher has difficulty with mobile performance, then AMP would provide an excellent method to get content into mobile search results quickly. Google has been candid that speed and performance are factors in how organic results are ranked, and should be a consideration when planning any mobile strategy.

Ultimately, the AMP pages are only as effective as they are visible. If a brand’s content is relatively static or not relevant to the news space, it’s not likely to be shown in the News Results where AMP pages appear most frequently. In addition, if a site is already responsive and performing well in mobile results, the efforts to build AMP content will not be a significant improvement. These factors must be weighed when deciding to commit energy to building AMP content in the current state of things.

Certainly the curtailment of JavaScript in service of page load times means that, at the very least, certain site owners will have to adapt to a new simplified standard enforced by Google. It also means that certain analytics platforms may be disallowed if they don’t meet those standards.

Moving forward, Google will likely encourage AMP expansion outside of the news publisher space and propagate it throughout the mobile web. At that point, sites using the framework could benefit even more substantially than they would by using it now, with page load time currently a factor in organic and paid placement on the results pages. Whether in several years this means that AMP is widely adopted remains to be seen, but regardless, marketers should continue to explore ways to ensure their mobile experience is as quick and efficient as possible.